Funding and Financing

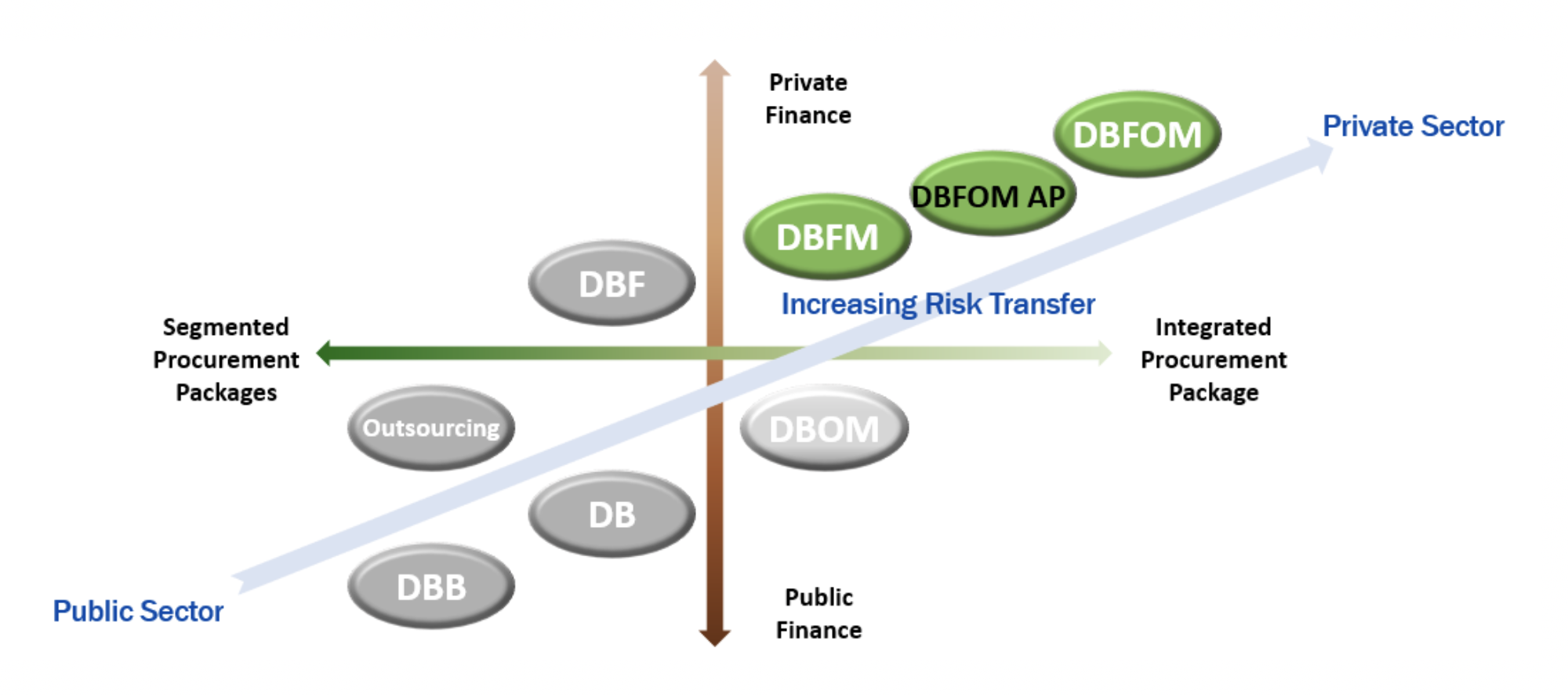

While this section of the toolkit is designed to inform on the funding and financing aspects of P3, focusing on finance costs alone misses the significant advantages that a P3 structure offers the public sector, such as the benefits of appropriate risk transfer, innovation, single point of responsibility, short and long term schedule and budget certainty, and matching long term revenues (tax or user fees) with long term expenses (availability payments). Owners should also consider developing, as part of the planning phase, a funding and financing memo (to be part of reference documents when issuing RFP).

FUNDING

Public money made available to the project. This contributed capital is not intended to be repaid or carry a cost (i.e. interest or return on investment).

Typical sources include:

- Taxes

- General fund

- Project/use specific (hypothecated)

- Funding programs

- User fee revenue

- Property development revenues

- State and federal grant programs

Each project is different and the way each project is funded is different as well. That funding will be determined by the structure of the project agreement. Some project agreement structures transfer demand risk to the private contractor. Under this sort of agreement, funding is provided by the rate payers with less risk of funding required, if any, from the public sponsor of the project. The availability payment, or ‘Take-or-Pay’ model of a project agreement places the demand risk on the public sponsor with that sponsor obligated to pay for the availability of water regardless if that water is utilized.

FINANCING

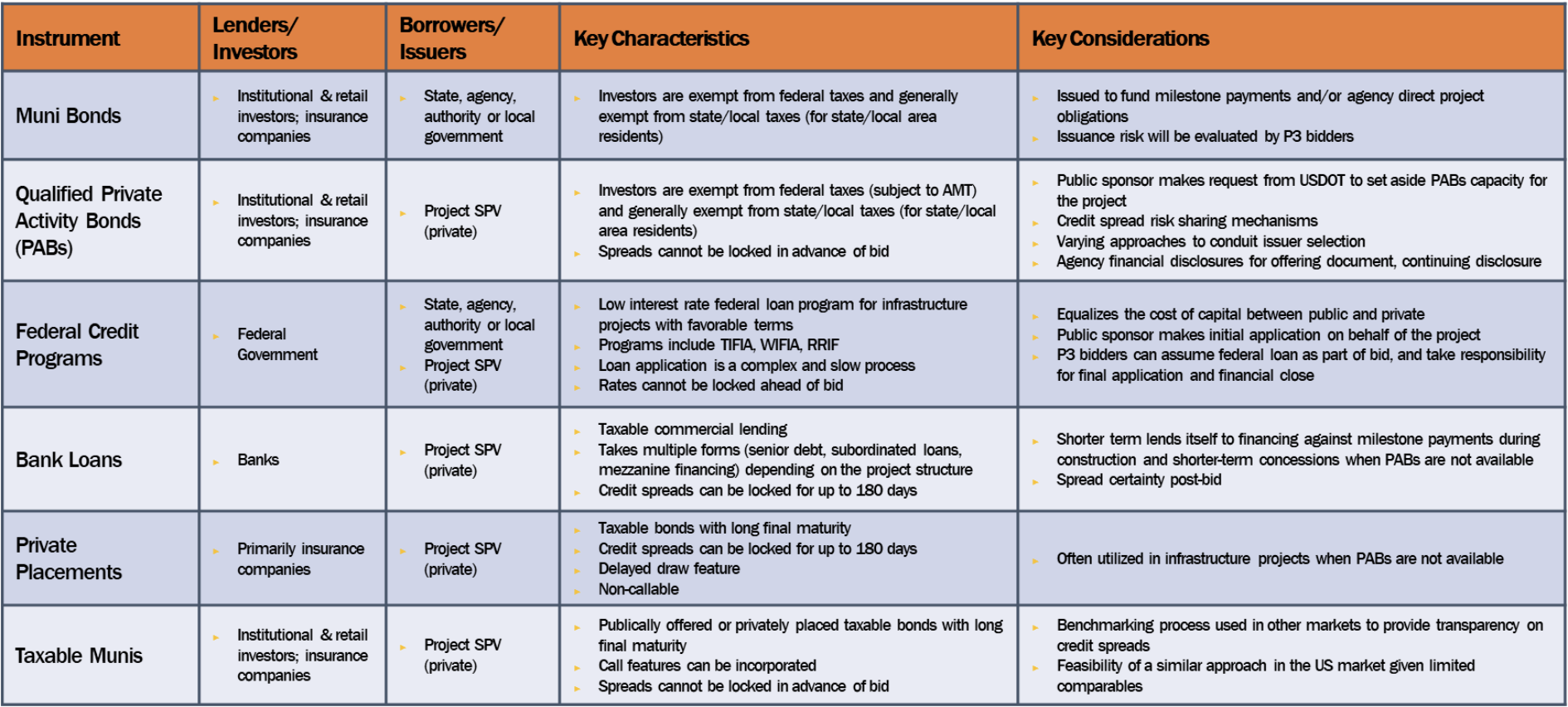

Money provided by private investors to pay for construction costs, concession payments and other large project costs. This capital is intended to be repaid and does carry a cost (i.e. interest and return on investment). Typical sources include:

- Debt

- Muni bond (tax exempt or taxable)

- Private placement

- Bank loans

- Equity shares

- Deeply subordinated debt

- State and federal credit programs

- Loans credit enhancement

It is important to note that a majority of the time debt and muni bond investors (those that buy the debt and are ultimately the lenders to projects) for projects which are financed directly by the public sector are the same as the debt and equity investors for P3 projects which include private financing.

FUNDING VS. FINANCING

The main difference between these is the risk that the investor is subject to (compared to the risk the owner retains) and that risk is readily quantified via the interest rate or equity return – the higher the risk, the higher the expected rate of return.

While there are similarities between traditional finance and public-private partnership water projects, the P3 model provides access to new financing opportunities. That access includes private activity bonds (PABs). PABs allow for the advantages of tax-exempt debt that can be mixed with the stronger oversight of private taxable investment.

Evaluation of all possible access to project funding or financing resources:

- Evaluate financing strategies, capital formation strategies and analysis

- Proposed financing plan, including projected revenues (public or private, debt and equity investments)

What is the mix of financial tools and sources that will be utilized for this project – and what are the different impacts on costs for each? A weighted cost of capital analysis will need to be completed to make the case for a P3 procurement. Does the public owner have all the data needed?

RESOURCES

The Water Finance Center provides financing information to help local decision makers make informed decisions for drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure to protect human health and the environment.

Water Finance Center Clearinghouse

A state revolving fund (SRF) is a fund administered by a U.S. state for the purpose of providing low-interest loans for investments in water and sanitation infrastructure (e.g., sewage treatment, stormwater management facilities, drinking water treatment), as well as for the implementation of non-point source pollution control and estuary protection projects. An SRF receives its initial capital from federal grants and state contributions. It then emits bonds that are guaranteed by the initial capital. It then “revolves” through the repayment of principal and the payment of interest on outstanding loans. There are currently two SRFs, the Clean Water State Revolving Fund created in 1987 under the Clean Water Act,[1] and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund created in 1997 under the Safe Drinking Water Act.[2]

Early in the implementation of the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund program, following the passage of the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act, EPA underwent a process of evaluating the adequacy of state public water systems. The agency’s goal was to devolve primacy for drinking water quality management to states that were prepared to accept the responsibility and to use the new funds provided by Congress in EPA’s budget to give states financial support.[3]

The procuring entity should look into other non-governmental sources of funding as they identify project needs. An example of this is Louisiana, utilizing funds from the RESTORE Act for their lock and dredging projects.

Contact AIAI for a list of advisors

The Role of Bonds

Rate payer and fee caps

- Project financing will be impacted by many factors, including the level of participation in the project by the public sponsor agency

- Owners as special purpose entities

- Joint powers structure